Earth Day Reflections: To See for the First Time

(from a speech first delivered at an award ceremony for Bay Nature Magazine)

There is a writer whose work I greatly admire, an ethnobotanist. His name is Wade Davis and if you haven't read any of his work, you are missing something wonderful. In One River: Explorations and Discoveries in the Amazon Rain Forest Davis follows in the footsteps of Harvard biologist Richard Evans Schultes who spent years in the Amazon cataloging thousands of plant species and discovering hundreds more while researching blight-resistant varieties of hevea for the U.S. government and a troubled war-time rubber industry. Among the many things that Davis does in this extraordinary book, is to introduce readers to two tribes: the Ika and Kogi of Colombia.

The Ika and Kogi see themselves as our “elder brothers,” part of a culture that is older, wiser—and as is often the case with the older and wiser—little appreciated, little understood. Among the Ika and the Kogi, it is customary in choosing future spiritual leaders to select a boy in infancy and keep him for 19 years in utter darkness. The boy learns songs, dances, stories, then the esoteric skills of meditation, divination and prayer. He is told about, but never sees, the exquisite beauty and dire complexity of the world. At the end of this period, he is taken out of darkness and shown the place about which he has been told so much.

Of course, nothing can prepare the initiate for that first breathtaking vision of the planet for which he has been designated steward. His reverence, respect and wonder at the full scope of creation are indelible.

Nineteen years of utter darkness is extreme. But I think the Ika and the Kogi have something to tell us about teaching someone how to see.

As a child, I spent years growing up under a wide blue Montana sky, cocooned in insecurity and stiff little dresses, a minuscule mote in a landscape where square miles were the yardstick by which distances were measured.

And I saw nothing.

I didn't see the way dawn touched the short black mountains, first with bruised periwinkle fingers, then with broad rosy palms, or how twilight withdrew reluctantly on long summer days, and nights unfurled, star-sequined and scented with the sharp green tang of pine forests. At the time, I didn't see much of anything. I saw the sidewalk under my feet, scored with my chalk marks, the asphalt under the wheels of my bike, and the colorful layers of my peanut butter and jelly sandwiches.

So, it is easy, given this simplicity, to remember a particular grade-school teacher, fond of her own voice. She'd read to us, the third grade class of North Star Elementary School, and among the things she read (most of them over our heads and obviously more for her pleasure than ours) were selections from the journals of explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. I think this was our history lesson or our lesson in social studies. Whatever the purpose, I remember the reading with great clarity. I remember it, because this is when I saw for the first time.

On Friday, May 31, 1805, Meriwether Lewis, canoeing along the Marias River in the vicinity of Great Falls, Montana, wrote in his journal,

"The hills and river Clifts which we passed today exhibit a most romantic appearance. The bluffs of the river rise to the hight of from 2 to 300 feet and in most places nearly perpendicular: they are formed of remarkable white sandstone ... the water in the course of time in decending from those hills and plains on either side of the river has trickled down the soft sand clifts and woarn it into a thousand grotesque figures ... nitches and alcoves of various forms and sizes are seen at different hights as we pass. the thin stratas of hard freestone intermixed with soft sandstone seems to have aided the water in forming this curious scenery. As we passed on it seemed as if those seens of visionary inchantment would never have and [an] end ..."

The teacher's voice droned on, climbing and descending like the river the explorers followed, and gradually, what had seemed to me to be flat earth against the flat pan of the sky, flickered magically and changed. The world grew round before me. As she read from those journals, I saw waterways with names like Salmon, Snake and Musselshell unwind to crawl over serpentine beds or plunge down precipices into granite basins. I saw a countryside teeming with wildlife—elk and buffalo and bear. I saw the trailing limbs of willows, tangles of vines, the tumultuous descents of waterfalls. I saw Indians. I could smell the buckskin. Now, as I blinked awake, seeing for the first time the panorama of my environment, I could also see what was missing—what was no longer there. It was a beautiful new world around me, but it wasn't the same as Lewis and Clark described it. Already much of it had passed away, buried in those meticulous accounts of elk and antelope shot; willow, cottonwood and box elder felled; choke cherry, sarvis berry, gooseberry and current stripped. But this did not trouble me at the time. The universe was brand new and fresh as it came streaming into me. I was absorbed in the first naming. That summer I watched a bear press paw pads on the windows of our station wagon at Yellowstone National Park and Blackfoot Indians dance in the shadows of blue glaciers in the Canadian Rockies.

Years have passed and I haven't lost my amazement or my awe at the rush of the world—like a great influx of breath—entering again, and I feel more acutely than ever, a sense of things passing. I'm still insecure and self-absorbed at times, still the girl in her stiff dress, carefully negotiating a course. Today, however, I cover my terrain with an explorer's inquiring eye, with the vigilance of a scout. But that old specter of transience still haunts me. I see that I live in a space far more cramped and congested than the generous territory of my youth. The world I live in is one where rainforests and barrier reefs are disappearing, where islanders invest in karaoke equipment to please throngs of visitors. Exploiters have replaced explorers.

Unlike the Ika and the Kogi, we live in a world of historical context. Our communications are profuse and immediate, as is our consciousness of the interrelationship of all that exists. We've seen what we often leave in our wake—homeless populations, spoiled wilderness. We can see the way the decisions and investments that we make, here, everyday, can effect just how much milk a baby in Uganda gets. Our world is a teeming, mysterious, multi-cultural mousetrap of a place where everything seems to hinge on something else. We share a new concept of this planet as a finite space, dense, and more difficult than ever to navigate. We live in an environment fraught with hazard, and it is important to have good guides, guides with insight—those who tread softly.

The Ika and the Kogi, those so-called "primitive" Colombian tribes seem to have this understanding. To teach someone—young or old—to see is nothing short of miraculous.

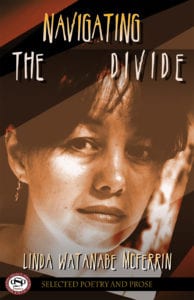

Linda Watanabe McFerrin's new book, Navigating the Divide, is to be the third entry in the ASP Legacy Series. It is due to release OCT 1st, 2019. NTD is a compendium of the best poetry, prose, and non-fiction writing from the stellar career of Linda Watanabe McFerrin.

"Reading Linda’s work is like being mesmerized by a snake before it swallows you whole. The words shimmer, creating a dreamscape where the story unfolds and draws you in while strange, sometimes bizarre, encounters play out in minutely described detail. You ‘emerge’ from her stories rather than ‘finish’ them. The poems are spare, elegant and evocative, stirring deep emotions even while not ostensibly emotional. This is a beautiful book by a writer who has honed her writing skills and knows precisely how to wield them."

—Maureen Wheeler, Co-Founder of Lonely Planet Publications

Pre-Order from Amazon Pre-Order from Barnes and Noble