When J.J., the narrator of That Paris Year, departed after finishing her exams, she left in June, too early to catch the extravaganza that is le quatorze juillet in Paris. But she knew about the legendary festivities she had missed in her adopted city: fireworks, parades, the laying of wreaths for the heroic dead—, with “le grand Charles” de Gaulle himself saluting from a grandstand.

J.J. already had her own, American-flavored July 4th sensibility, as she remembered lighting sparklers and pinwheels while eating home-made peach ice cream in Gran’s garden before migrating to the big celebrations downtown with bursts of fireworks and music near City Hall.

From her intense study of history at the Sorbonne she knew that the two National Days were linked by their common late-Eighteenth-Century struggles to overthrow tyranny, establish a democratic form of government, and champion the rights of man. The Americans got to revolution first (1776), while the French soon followed (1789). But the American Revolution, and the basis of its founding documents, drew heavily on Enlightenment thinking, inspired by the French philosophes Voltaire, Rousseau, and Montesquieu, whose book “L’Esprit des Lois,” (The Spirit of Laws) led directly to the structure of our three branches of government with its concept of the balance of power.

Indeed, J.J. knew all this, as well as the more obvious similarities in both her French and American roots: the red, white and blue flags, the rather unfortunate choices in national anthems, the female figureheads that symbolize each country. Three horizontal stripes comprise the French Tricolor, while of course our own adds a busy field of stars to its stripes. As for the anthems, La Marseillaise, highlighting the storming of the Bastille, is frankly blood-filled, calling for raising the “bloody standard” and for citizens to take up arms and march. The Star-Spangled Banner, meanwhile, composed during a naval battle of the War of 1812 similarly touts “bombs bursting in air,” and the tune of the former drinking song reaches musical notes suitable for sopranos in good form, if not the masses. The well-known post-revolution symbol of France is Marianne, a personification of the Goddess of Liberty, who represents reason and the three principals of liberté, égalité, fraternité. Our own Statue of Liberty is also a version of a Roman Goddess of Liberty, Libertas, which is inscribed with the date July 4, 1776, and has stood in New York Harbor since 1886 as a beacon of liberty, welcoming immigrants. She, of course, was a gift from France.

In the years since 1963, J.J. might well have witnessed other celebrations of Bastille Day, either in France or abroad. I certainly have. One memorable day was in Strasbourg when my children were small and we stood in astonishment as missiles rumbled down the street below the balcony of our hotel, while fighter planes nearly buzzed us from above. Or another occasion, a friend and I arrived from the Canal du Midi in her boat in time to see a spectacular display of fireworks over Carcassonne, the ancient walled city in Provence. Wanting to continue in the spirit of the day, we anchored and went to the festivities in the modern town square, which, to our surprise, consisted of a night long tribute to The Beatles. Everyone danced and sang all the words in English.

Dancing and singing seem to have been a part of the French idea since it’s beginning. On July 14, 1790, the first celebration, the Fête de la Fédération, was held a year after the storming of the Bastille to symbolize peace. It took place on the Champ de Mars, then way outside Paris, and required a huge amount of construction to accommodate the crowds. In order to get the work done, thousands of Parisians showed up voluntarily to finish the job. On the great day, despite pouring rain, 260,000 citizens turned out, as well as a Who’s Who of celebrities. Bishop Tallyrand conducted a mass, General Lafayette took his oath to the constitution, as did King Louis XVI, still in possession of his head. Thomas Paine and John Paul Jones were also there, unfurling the Stars and Stripes outside the United States for the first time. It is said that the official celebration was followed by four days of partying, fireworks, feasting, fine wine, and running through the streets naked in the name of freedom.

J.J. might well have enjoyed that first pass at Bastille Day; as a child of California, some of the festivities would have been familiar. But if one could go back in time and witness only one Bastille Day, I’d say the one to pick would be July 14, 1945. Nearly a year after the liberation of Paris from German occupation, the end of the nightmare war was in sight. The slow process of recovery had begun in France. There was order in the streets, the eternal flame was burning under the Arc de Triomphe, triumphant troops marched down the Champs Elysée, le Grand Charles was there, of course, fireworks exploded and the lights were blazing on the Eiffel Tower. It was, I understand, a moment of renewal and commitment to the principles of the revolution, to a democratic republic, to liberty, to the rights of man.

Had J.J. witnessed that day, she might have found hope that July fourth could also symbolize such meaning again after long seasons when the lights went out.

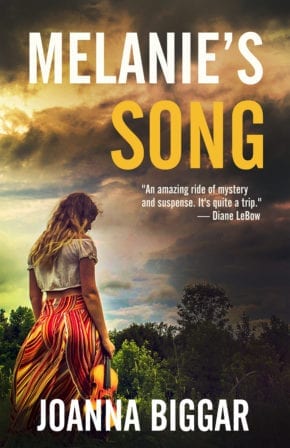

Joanna Biggar has traveled solo in the most remote areas of China, chaired a school board in Ghana, worked as a journalist in Washington, D.C., and taught school kids in Oakland, California. She is a member of the Society of Women Geographers, mother of five, grandmother of eight, all of whom love books! Joanna’s first novel, That Paris Year, is written in English but captures that French novel feel in a truly classic style. If you’ve been to Paris, she will welcome you back, if you haven’t, you may just want to pack your bags! That Paris Year is a truly splendid read! In Autumn of 2019, we will follow Melanie, the heroine of That Paris Year, to California in Joanna’s long-awaited sequel, Melanie’s Song.

Set in the era of Woodstock and Watergate, Melanie’s Song centers on a young woman’s mysterious disappearance, and on her friend’s determined search for her.

Melanie, who fled her marriage to a straight-laced classical musician in order to hitch-hike to Woodstock and San Francisco, was last seen at a commune in the California hills. Rumors abound: that she took up with a Black radical; that she had his child; that she and her lover, armed, ran a bank heist a la Patty Hearst; that she developed a mystical gift for spiritual healing; that she died in a possible accidental, possibly staged commune fire.

Trying to sift truth from invention pulls her friend, the young reporter, J.J., into the underbelly of the sexual and social revolutions of the 60s and early 70s, where she encounters corrupt cops, paranoid hippies, activists, mystics, drug-runners,and most astonishingly, Melanie’s own parents. Risking her job, her connections, her life, J.J. follows Melanie’s trail, determined to find out what happened to her once-compliant friend now turned, it seems, into a rebel angel.