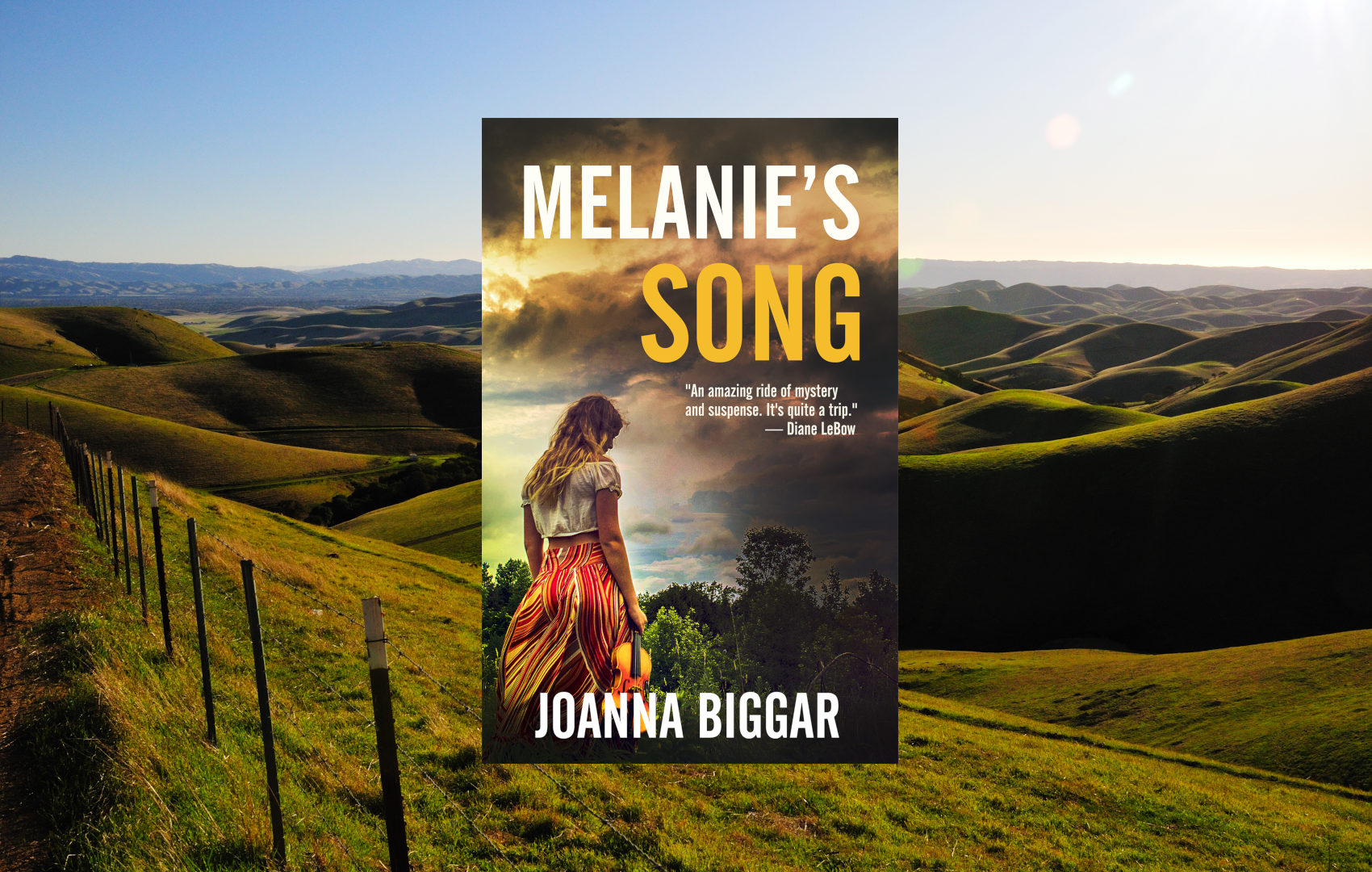

Joanna Biggar Reveals the Heart Center of her Newest Novel

Novelist Joanna Biggar opens up about her latest novel "Melanie's Song," its impotant relationship to the setting, California, and its place in her body of work.

After 2015's That Paris Year which followed a group of young women on their year-abroad at the Sorbonne—their youthful flings as well as their many rites of adulthood— Joanna Biggar has brought its spiritual sequel Melanie's Song back overseas to her own hometown in the United States. Set in Califonia amid the cultural revolution of the late 60s early 70s, Melanie's Song, while not a direct sequel to That Paris Year shares many of its characters and its familiar, lavish lyrical style. In MS, J.J., the protagonist of That Paris Year, a young reporter, is on a quest to find her missing friend, Melanie (the archetypal shy scholarly type and another character from TPY) who fled her marriage to a straight-laced classical musician in order to hitch-hike to Woodstock and San Francisco.

Rumors abound: that Melanie took up with a Black radical; that she had his child; that she and her lover, armed, executed a bank heist; that she developed a mystical gift for spiritual healing; that she died in a possibly-accidental, possibly-staged commune fire.

Trying to sift truth from invention pulls J.J. into the underbelly of the sexual and social revolutions of the 60s and early 70s, where she encounters corrupt cops, paranoid hippies, activists, mystics, drug-runners, and most astonishingly, Melanie’s own parents. Risking her job, her connections, her life, J.J. follows Melanie’s trail, determined to find out what happened to her once-compliant friend.

We sat down with Joanna Biggar to talk about her latest novel, its relationship to her past work, and hosting its geographical and thematic heart in her hometown of California.

ASP: Melanie is the least rebellious of the five women in That Paris Year, as well as the most insecure and the most eager to please. Her transformation in this book comes as a big surprise. Can you talk a bit about how the character evolved from dutiful daughter to a commune-living fiddle player?

Joanna Biggar: True enough. Like the others, she struggled to find who she really was as she distanced herself from her cold, materialistic, socialite family, and tried to find her place in a relationship with a gifted young violinist who worshipped her mostly as “muse.” She sought to find recognition for her scholarship, for her thoughts, but she was chased for her body. Her disappointments allowed her to see the plights of others in misery but out of her milieu: namely the poor and dispossessed. Beneath her exterior of polite respectability, a social and political consciousness began to grow. Once home, she was ripe for shedding that exterior when it no longer fit and for joining the tide of the counter-culture as it ripped across the country. I certainly knew people who also jumped in, seeming to change character completely. It has been interesting over time to witness ways in which they have changed back.

ASP: You brought back a few characters from That Paris Year, specifically I know of Evelyn and J.J. returning. But it is not an ensemble like it was in That Paris Year. This is very much Melanie’s story. How necessary is it that the women should stick together in some way?

JB: My concept of the young women being almost organically tied to each other through the formative process of finding their identities, means that in some way, like long-distance quintuplets, when one moves the others feel it. Just as Melanie reflects and comments on where each of them is in her life, so they reflect on hers, try to figure where she is and what she is doing. They share their stories and thus help define her as she seems more elusive, even as she reflects on them in her journals. Like her, they, too, find their way back to California because they, too, are its children, born of its soil.

"She sought to find recognition for her scholarship, for her thoughts, but she was chased for her body. Her disappointments allowed her to see the plights of others in misery but out of her milieu: namely the poor and dispossessed."

ASP: The narrator of both books, J.J., is a journalist, and that character is also the “autobiographical” one – you were a working journalist for many years. I would love to hear how the role of chronicler carries over from your life to the novel. Why is it so important to J.J. and to you to get these stories of women’s lives into print?

JB: To answer this question is also to touch on several others. The idea for these characters and books was conceived decades before they were finally written. I was very interested in the way close connections between young women can lead them to “try on,” or even adopt each other’s identities. An experience as ground-shaking as a year in a foreign country brought such questions into sharp relief, and as my fictional world began to coalesce around my experiences as a foreign student at the Sorbonne, the autobiographical “I” as narrator was formed. That narrator, J.J., wanting to understand the shifts in her friends’ lives, in her own life, and in their perceptions of reality, declared herself in search of the truth. Truth she supposed was to be found in the facts more than the poetry of experience, where her basic instincts lay. It seemed logical such a person would become a journalist. So I put her on that path in early drafts, years before in fact I became one myself. This may be a case where a writer becomes her character, rather than the other way around.

ASP: J.J. has to fight to be assigned serious stories by her editor, Bud Purvis, and early in the book, is actually demoted from the Travel section to the Women’s section. Can you talk a bit about what it felt like to be a working woman journalist in the 20th century? Did you see yourself as a trailblazer? Did you have mentors —like Alice is to J.J. in the book — who lent a hand along the way? How important is the friendship of other women to your own writing career?

JB: I didn’t really begin my career as a journalist until the early ’80s after coming back to the U.S. with my family after several years in Africa. Up to that point, I always imagined I would be teaching literature (French of course). I did have wonderful women who were my mentors along the way. One, Luree Miller, was so helpful she even lent me her downtown D.C. office and gave me her notes on a story she said she didn’t have time to get to! It helped launch my career with the Washington Post. She also sponsored me for membership in the Society of Woman Geographers, a group of extraordinary women explorers whose company I cherish to this day. Another wonderful mentor was Gwen Gibson, whom I worked with at the wire service, Maturity News Service. A former writer for AP and the Herald Tribune for whom she covered the Kennedy White House, she knew everybody and was generous to a fault. She even lent me her number at the Washington Press Club so I could go in, pretending to be her. I consider these women, a generation ahead of me, to be the real pioneers in journalism, and I absorbed many of their stories. I have to say that, although I did certainly encounter Bud Purvis types, I also was given huge encouragement, direction and opportunity by several men. I remain very grateful to them all.

"Luree Miller, was so helpful she even lent me her downtown D.C. office and gave me her notes on a story she said she didn’t have time to get to! It helped launch my career with the Washington Post."

ASP: You taught a creative writing course for years called “A Sense of Place,” and the sense of place is strong in both of your novels. Can you talk about what California, particularly northern California, has meant to your growth and development as a writer?

JB: "Sense of Place" was a title I shamelessly borrowed from Lawrence Durrell, one of my favorite writers. In the title essay of the book, he makes the distinction between a tourist and a traveler: the former being one who passes through a landscape unchanged, and the latter being a person who can inhale the air, taste the wine, hear the music and fold into a new country, psychologically as well as physically. Of course, I aim to be a traveler. But I also believe profoundly in the influence of that primal place, the place where one is formed. Certainly for me that place is California, and although my childhood was in southern California, I have spent much of my adult life in the north, and find an overarching identity in the whole. (Heresy to partisans of one or the other). We have a Mediterranean climate and a lifestyle that is more compatible with similar places in the world than with the other parts of our own country. We are historically open and welcoming to innovators, risk-takers, rascals and reprobates of every sort. While our history includes racism and repression as it does in all parts of America, still we have been a “mixed-race”—Native American, Spanish, Mexican, Chinese, Japanese, South American, and every sort of European—from our beginnings. Most importantly, East Coast kinds of family and social connections do not count here as much as individual worth or achievement. And we are connected north and south by muscular mountain ranges, enormous valleys providing agricultural abundance, and a thousand miles of magical coastline. If I had grown up elsewhere, in the East for example, where my family in America began, or in the Midwest, where they migrated, I think I would be a very different person from one who had tossed in the surf from the age of three and, on occasion, eaten Thanksgiving dinner next to a rambunctious stream under spreading live oaks.

ASP: Furthermore, California in the 1960s is both in a way a reflection of the liberal shifts happening in France prior and a foil to it, being both geographically and culturally quite removed from France. What went into the decision to carry Melanie’s story into the American West?

JB: Certainly there are many connections between California and France, and a great affinity between the two. At the time of Melanie’s Song, the currents of rebellion had crossed back and forth again between them as they have since the American Revolution. Nineteen-sixty-eight had been a year of upheaval for both. Melanie’s journey during that time does find its way across the land; first from her isolated view of the 60’s revolution from Rochester, NY, then eventually to the cultural maelstrom of Woodstock, with political and love interests running into the South. But Melanie is a Californian, and it is her native ties there as well as the lure of true freedom that brings her back to flower into the free spirit she becomes while the California version of the revolution flowers around her.

ASP: The prose in That Paris Year is limpid and sensuous, much like the works of other noted French novelists— Proust, for instance, you mirror, in long, unwinding sentences. But now your setting has shifted to the Americas and so has your prose style. In what way is this shift in prose style a companion to the shift in setting?

JB: I have consciously tried to adapt each [style] to the type I perceive it to be. Actually, That Paris Year does draw on the Proustian tradition of long, unwinding sentences, as you say, and the words that probe the twists of time and memory, while Melanie’s Song tries to find language suitable to the mystery and the uncut dialog of some new and rough-hewn characters. Finding the right language for the third novel centered on that most explored subject of all, love, will be a huge challenge.

"But Melanie is a Californian, and it is her native ties there as well as the lure of true freedom that bring her back to flower into the free spirit she becomes while the California version of the revolution flowers around her"

ASP: I understand that you’re fluent in French and English and have spent a significant amount of time in the US and Europe. So I wonder in which idiom you feel more comfortable writing?

JB: I have a Ph.D. in French literature and have spent as much time in France as I could over many decades. With each return, it takes me a bit of time to fall easily into the fluency of both hearing and speaking. But the more time I spend there, the more immersed I become. I understand I’m completely “there” when I start dreaming in French. After a long period of time, a funny thing happens, and I realize I can find a word in French while having to dig for it in English. Of course, after long stretches away, the reverse happens. But whereas my speaking (with an unknown accent once identified as Yugoslavian) and writing French both become more fluid over a lengthy period, unquestionably English, my langue natale, as the French call it, comes most easily to me for writing.

ASP: Being a travel-writer and having much experience writing about and on what a fiction writer might dismissively call "settings", would you say that you look for a place to fit your story to, or that you find your story in (or from) a location?

JB: Travel writing is many things. For me, in its best sense, it comes from a long process of knowing, growing and immersing myself in a place—from living there. I have been able to so that for very long periods in France, in Ghana, and for a shorter time in Costa Rica. The travel writing that emerges from a trip, whether with our group of writers, or from many trips I made as a journalist on assignment, is of shorter duration and a different perspective. Normally I try to steep myself in the history, culture and writing of a place before I go to have some bearings. The experience of being there often overrides those preconceived notions. And the best travel writing I have done, I think, comes from some connection I find to my own life. We call these pieces “personal essays,” but they reflect the idea that travel is a two-way street of give and take. I have found this to be true in remote China, in the Sahara, in Indonesia or in the equally (to me) exotic landscape of North Dakota. In my view, the story arises from the place, from the land itself, and cannot be imposed.

ASP: Does writing about a place ever change your outlook on/initial impression of that place?

JB: I am very interested in the role of memory in our lives, and its fluid nature. The act of writing something fixes that subject, place, or character in a particular time frame, so to pull it out of a continuum of time is itself a kind of distortion. And just as I have had the experience, as many writers do, of a story or character take on a life of its own and go in a different direction, I think the act of writing is also an act of invention, often with an unforeseen end. So, since writing is about adding layers and perspectives to its subject, the first impression (which I try to hang onto as an authentic moment) becomes but one of many. Yes, revisiting a place or situation through writing changes my view of it just as revisiting the place—or the “scene of the crime”—inevitably does too.

"I am very interested in the role of memory in our lives, and its fluid nature. The act of writing something fixes that subject, place, or character in a particular time frame, so to pull it out of a continuum of time is itself a kind of distortion."

ASP: This is the second novel you have written exploring the lives and relationships of a particular — and particularly interesting, innovative, and powerful — group of women friends. Are there plans for a third book on this topic?

JB: I always envisioned a trio of books revolving around the same core group of characters as they move through time. The third novel will return to France and focus more on the life of the narrator, J.J., although the other characters will certainly play into it. However, in this book, J.J. reconnects with her old life in France as well as with a Frenchman, at the same time trying to find the story of the lives of her grandparents, which takes her back to WWI. If That Paris Year is at heart a poetic journey of discovery and Melanie’s Song is at heart a mystery, the third book will be a love story.

Joanna Biggar has traveled solo in the most remote areas of China, chaired a school board in Ghana, worked as a journalist in Washington, D.C., and taught school kids in Oakland, California. She is a member of the Society of Women Geographers, mother of five, grandmother of eight, all of whom love books! Joanna’s first novel, That Paris Year, is written in English but captures that French novel feel in a truly classic style. If you’ve been to Paris, she will welcome you back, if you haven’t, you may just want to pack your bags! That Paris Year is a truly splendid read! In Autumn of 2019, we will follow Melanie, the heroine of That Paris Year, to California in Joanna’s long-awaited sequel, Melanie’s Song.