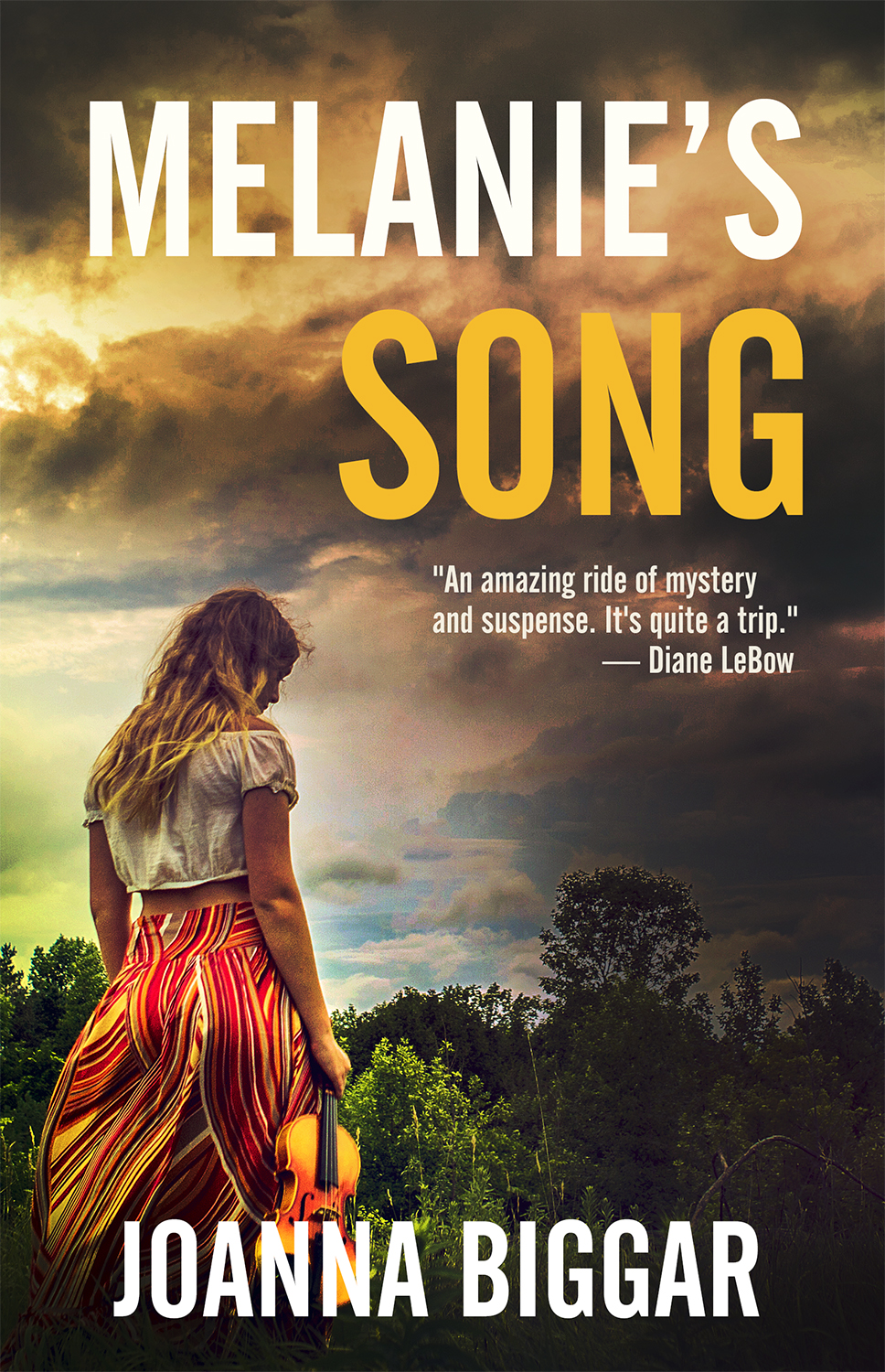

Joanna Biggar Presents a Chapter from her Upcoming Novel

In the fifth chapter of "Melanie's Song" we "encounter a gathering of personalities and links that will weave into the fabric of the novel."

At the beginning of the fifth chapter of Melanie's Song, we find J.J. leaving Mendocino after her first visit, as both friend and journalist, to investigate the burnt-out commune in the forest where her missing friend, Melanie, was rumored to have lived. Soon we also encounter a gathering of personalities and links that will weave into the fabric of the novel. We meet some of those tied to the continuing mystery that unfolds on the Mendocino coast, from the off-putting huge personality of bear-like Moon, to the snivelly cafe server, Pigeon. We also see first-hand J.J.’s misogynistic, buffoon-like newsroom chief, Bud Purvis, in action.

But more importantly, we begin to get a sense of a powerful collection of women across generations who influence and embrace J.J. Mother figures, including her own mother, Anne, who collects too much and says the wrong things; her editor, Alice, who is experienced, wise, challenging, and always has her back; and even Mama Cass, café owner and look-alike for the pop singer of the same name, whose role in J.J.’s life keeps evolving. We find her “sisters,” too, college mates, friends, fellow voyagers to Paris, among them Melanie and Josephine, to whom she feels spiritually bound. And finally, we see yet another generation and sense the strong pull of another central figure: Gran, J.J.’s French-born grandmother.

And in the background, there is the music of her generation, which declared that “music is the revolution.”

—Joanna Biggar

J .J. knew when leaving Mendocino it was best to head inland, go over the coastal range to Boonville, where Ivan had found Melie’s journals, and crash there for the night. Boonville was, after all, part of the story, the place where Ivan had discussed Melie with that guru inhis flophouse. The reporter in her said it was a place to check out further—and it also put her on the way to Highway 101, the fastest route south from the Mendocino coast. But Melie filled her head. Going into the dark forest and poking about in the spot Melie had once stayed seemed a bleak and for-bidding prospect. As sorrowful friend instead of working reporter, she took the coast road. The light will last longer, she told herself for justification, keeping to the winding road by the sea. I really don’t want to be in charge of this disaster, to think about who to call, who to tell...who to question. With that thought, J.J. jammed a Joni Mitchell tape into the cassette player. Perfect, she smiled to herself as the clear voice called out the warning, “I couldn’t let go of L.A., city of the fallen angels...”

By the time the Datsun pulled into an oceanside motel south of Gualala, it was dark. Once inside her small room, J.J. opened the window and let the sounds of pounding waves lull her to sleep. It was still early morning when she turned inland at Jenner to follow the Russian River and reluctantly parted company with the sea. Glancing at herself in the rearview mirror with windblown hair full of salt, she saw her face shining pale beneath dark brows in the reflected light. God, she thought, frowning and reviewing her nondescript loose blouse over a long, creased jean skirt. What a mess. Bones? Hah! More like lumps and wrinkles. No lady reporter look going on here. With hours of freeways stretching numbly in front of her, J.J. willed herself not to think of Melanie, her notes and journals, her fate—and also what a potentially big story she had stumbled into. She just wanted to lean into music, for her mind to be quiet, blank, and “to fix on something nourishing,” as Gran would say. Suddenly Gran’s garden, with its crazy juxta-positions of palm and avocado and orange trees, its ferns in huge pots and trellises with sweet peas, its flat beds of daisies and nasturtiums and ranunculuses, its sunny side porch where terra-cotta pots filled with lavender and red geraniums made visible Gran’s Provençal roots. Its riot of colors and shapes played in her mind. She saw a child run- ning barefoot through the sprinklers, making wet footprints on the smooth cement paths, watching butterflies drift lazily around bright petals.

Gran’s back fence, Gran’s house. Gran’s kitchen, with its aromas of herbs and olive oil. The past. For all practical purposes, Gran’s house was her house now. Or more accurately, Gran’s house without Gran, because Gran lived nearby in a “residence” but didn’t really reside there either, because she didn’t reside inside herself anymore. J.J. clutched the wheel tighter as she headed toward the inevitable, dreary I-5, trying forcibly to prevent herself from thinking about the grief of losing Gran piece by piece, of the awful decision she had made—they had made, for when Gran was lucid enough, she’d agreed that she couldn’t remain at home any longer. She needed more attention than J.J. could give in the time left after work and travel. Gran needed more than help with dressing, meals, the every-day things of daily life; she needed someone to watch her every minute, someone to keep her from wandering. J.J. had wanted, at first desperately, to hire someone, to have a “keeper” full time at home. But it would have been just that, a keeper, and Gran would have been a prisoner in her own house.

When Gran was lucid she knew, far better than J.J. could understand, what needed to transpire. “There are times in one’s life when it is the moment to leave one place, one phase, and move to the next, n’est-ce pas, chérie? Non, ma petite,” she went on, “it’s no use to rattle about this big house alone, and non, non certainly not with a pair of strange eyes watching me all the time. It is best now for a place that is...cozy, non?” She smiled that soft, dreamy smile that had always calmed J.J. and as a child had made her think of faraway places. “Besides, ma petite chérie, it gives me such comfort to know you are here, and to think I can come home whenever I wish. When you are home too.”

J.J.’s heart had missed a beat, for then she knew. Gran had never once said it in so many words, she had never even faintly complained at her granddaughter’s long hours and absences since J.J. had given up her apartment to move in with Gran more than two years earlier. But with that phrase J.J. at least glimpsed the loneliness of Gran’s isolation as she lived more and more within the confines of unraveling memory. I am her world now, J.J. had acknowledged. For reasons J.J. never fully comprehended, she and Gran were close in ways that Annie and Gran never had been. I am what she hangs on for. I am home.

Facing the hot barrenness of the highway, J.J. needed to make a plan. Gran first, she thought. I’ll go to the residence, sit and have supper with her, or tea after dinner while she rocks in that wicker rocker we brought from home. If Gran was up for it, maybe she could come home for the night, stay for a spell. Of course, Gran might not be up for it, might be in that vague space where the old familiar smile seemed to mask an entrance to a new, unfathomable place, or she simply might not communicate at all. That’s how it was now, you never knew where Gran might be.

Then another idea came to her. Drop in on Mom. Or Annie, as she always insisted, Annie, short for Antoinette, and mother not a concept or a name she had ever been particularly comfortable with. Okay, drop in on Annie...whoever.

Especially now, with Gran in some sort of permanent twilight, it was important to lessen the gulf that had always existed between her mother and herself. After a bout of what J.J. knew had been reckless complaining, Alice had once chimed in: “Despite herself, despite her obsessions and possessions, your mother does have a streak of empathy, you know.” Maybe now was the moment to test it. Maybe Annie would be the one to offer comfort for the stress of confusion, loss—of losing Melanie.

But getting to Annie’s, all the way in West L.A., was the problem. And a crap shoot as well just to go to that jumble of a house, which never seemed to unclutter despite the fact that so much of the junk—“unique collectibles” Annie called them—wound up in her trendy shop in Brentwood. “It’s all the rage with the rich, famous, or aspiring to be. Annie’s Ark, the place to see and be seen, like a club along the strip. It’s even turning up in the gossip columns,” Annie had reported triumphantly.

Okay, J.J. reasoned, maybe not Annie’s. Maybe I should see Dad first instead? Or would he be with Annie? If so, would they still be fighting about the fact, still quite incredible, that her middle-aged, mild-mannered father had moved an acting student who looked hardly a day over eighteen into an apartment in Santa Monica? The fact that he had met her at a sleazy bar where she worked as a hat check girl in a costume leaving little to the imagination hadn’t bolstered his case that she was just “a sweet kid who needed a break.”

J.J. recalled the aftermath with a slight shiver. Annie, her empathy button definitely turned off at that news, had yelled: “To hell with all this peace, love, go-with-the-flow shit,” and things began flying. An empty picture frame, a milk glass pitcher, and a few Chinese rice bowls barely missed him as he ducked. Later, his listed crimes included “the loss of irreplaceable precious objects.”

After slinking back to the apartment and assuming his absent posture, he had tried to tell his version of the story to J.J. “Annie,” he said, summoning his worst epithet for his wife, “has been acting French again.”

Remembering all this, J.J. shifted her weight in the seat. Joni Mitchell sang “Black Crow” on the tape deck. “I’ve been traveling so long/How am I ever going to know my home/When I see it again...” The possibilities racing through her head finally turned off. Checking in with her crazy relatives wasn’t going to bring any relief from her angst about Melie, and she knew it. She also knew what she really needed to do. See Alice.

J.J. KNOCKED ON the beveled glass door of Alice’s small office, feeling as if her head would split.

“Come in.” Alice’s eyebrows arched in anticipation over her tortoise-shell glasses, pencils stuck in the bun atop her head. Alice looked like a school principal, and J.J. had long concluded it was impossible to know how old she was. Old enough at least to have come up the ranks before the word “feminism” was uttered with meaning, old enough to go head-to-head with the likes of Bud Purvis and walk away with a tight victorious smile on her thin lips whenever required.

Uninvited, J.J. sat, and Alice, sensing something more than usual amiss, pulled her glasses down on her nose and ceased her normal twitching, ready to listen in silence. “Okay,” she said, “let me have it.”

There were a few clarifications as J.J. spilled out the entire story.

“Wait, so there was yellow police tape around the fire site, but nobody present?” Alice wanted to know.

“Correct,” J.J. answered.

“This Moon character, no other name?”

“Not that I know of.”

“Wait,” Alice raised a hand to stop J.J. at one point.

“Tell me I didn’t hear what I thought I heard, that you got in a truck with this creature.”

“Actually, yes,” J.J. replied. “But he was harmless. I’ve got a good sense about these things.” Alice rolled her eyes.

The recitation finished, Alice’s eyebrows arched like a cathedral spire, and she said “Oh my God,” in a quiet monotone.

“Let me get this straight. We have a missing friend, who more than likely has turned into a missing person and quite possibly a body in a mysterious fire in a hippie commune. We’ve got a bear-like creature named Moon, a fat-assed café owner and possible conspirator named Mama Cass, a missing—this word keeps coming up, I notice—witness and source named Cat, who somehow has come down with a baby. Am I forgetting something?”

J.J., noting Alice had switched to “we,” shook her head no.

“Well, of course I am. I need to say it loud and clear: we’ve got a hell of a story, J.J., you know that, don’t you?”

J.J. nodded, not wanting to get into how it was so much more than that for her.

“Mind you, breaking news in Mendocino is slightly beyond the normal interest of the Pasadena Star.”

“Yeah,” J.J. agreed. “There is a local angle, though. Melanie is a Pasadena girl. Her parents still live here.”

Alice sat uncharacteristically still for a moment as she knitted her eyebrows into a question mark. “So what do you want to do?”

J.J. took a long time to reply. “Same as I wanted when I went up there last weekend—to find out what has happened to Melanie. To know the truth before I begin writing it.”

“Okay. Fair enough. So what we need is to figure out a way to keep investigating this without having a dragon breathing down our necks,” she gestured to Bud Purvis’s office, “pressuring us to publish before we’re ready. What if somebody else breaks it first?”

“That’s a problem,” J.J. acknowledged. “But it’s necessary to have whatever time it takes to get this right. More than I can ever remember, I want certainty of a high order on this one before going into print.”

“Right.” Alice shoved her glasses back up in front of her eyes. “What we need is a strategy.” She thought a moment. “What are you working on now?”

“That Hollywood fashion show thing.” J.J. sighed.

“Aha, got it!” Alice slammed her palm on the desk in triumph. “We go with some ‘homespun threads and hippie trends piece’ prevalent on the North Coast, pitch it as a counterpoint to the Hollywood style. So go to Hollywood, my dear, make it sparkle, and I’ll take care of the other end.” She jerked her head toward Purvis’s door once again.

J.J. HEADED WEST on the narrow entrance lane to the Pasadena Freeway—First Freeway in the Nation, the city fathers boasted—with a familiar well of restlessness rising in her. She blocked out the press briefings she’d scanned earlier that would define the day ahead: bimbos in grotesque makeup parading around in miniskirts and versions of go-go boots that had been around already for nearly a decade, at least since Nancy Sinatra had immortalized them in song. Then some radical “protester chic” thrown in for counterbalance. And of course interviews to arrange, and a photoshoot. She glanced at the freeway signs and saw the turn- off for Melanie’s parents’ house. The whole fashion charade seemed even more grotesque now that Melie was missing, and perhaps... She couldn’t finish the thought. Her mind drifted to getting in touch with the frosty, difficult Harts.

Nearing Hollywood, the image of Jocelyn—clad in the very miniskirts and high boots that she had to cover now—jumped up at her from a large billboard. For an instant, J.J. fantasized about bagging her studio fashion show assignment and heading for Jocelyn’s house and demanding to be let in. Then she remembered what she had to do and gunned the motor.

By midafternoon, back in the office banging out her notes on the newest model IBM Selectric, she felt nervous indigestion. The typewriter had been a peace offering, of sorts, from Bud Purvis when he had first pulled her from Travel, declaring that he would give the Women’s Section, for God’s sake, one of the first new expensive machines with its signature instant correction feature, no erasures, no mess. “No excuses for any fuckup now, J.J.,” he had said with an unrepentant laugh. But at least he no longer smoked cigars in the office, and he no longer called her sweetheart. What was he going to do now, when Alice hit him with their scheme?

A week later and the first draft of “Hot Styles among Starlets” was done. With enough time to go before deadline, J.J. drifted from her uncluttered desk to the window. Fidgety, and knowing Purvis was stingier than ever these days about travel money—he himself was being squeezed by the money boys, as he called them—J.J. worried that he’d cut her funding for travel. She paced, watching the mindless traffic of Colorado Boulevard move back and forth in the afternoon smog. She tuned out the clacking of typewriters, the ceaseless jangling of phones, the banter and jokes of the newsroom to peer out the dirty window. Images of boots and miniskirts and outsized belt buckles and flowing bell-bottom pants blurred her reflection in the glass. It all seemed so banal, Hollywood and fashion crazes and movie star worship. She swallowed with a trace of bitterness. People were out there dying, in wars, in the streets. People out there were disappearing.

Finally, she settled down enough to polish her piece, then presented herself at Alice’s door. “I have copy,” she began.

Alice skimmed through it quickly. “Fine, okay,” she pronounced. Then, with a sweeping movement of her hand toward Purvis’s door, said, “I’ll handle this now.”

J.J. returned to her desk in time to hear, “Jesus H. Christ, Alice...” erupt from his office, and plunged into her files, trying to look busy. A few minutes later, she felt a hand on her shoulder and looked up to see Alice.

“Well?”

Alice greeted her with a tight smile. “You’ve got to the end of next week and the weekend’s your own. Be back Monday. Two pieces on the raggedy-muffins and their rainbow rags. So go for it.” J.J. blew a kiss as Alice waved, turning on her heel.

On impulse, J.J. picked up the phone to call Bread & Beads before leaving. She could justify the expense by claiming she needed to consult Mama Cass about “full-figured fashion,” if Purvis objected.

After dialing the operator and waiting impatiently for the long-distance wires to connect, at last the repetitious honking sound began to reverberate in the receiver. “The line is busy,” said the operator in the requisite nasal voice, “would you like to hold?” J.J. held.

“Bread & Beads,” a voice suddenly squawked on the other end of the phone she still clutched, sounding a thousand miles away. “May I help you?”

“Hello Pigeon,” J.J. answered, hoping the familiarity would disarm the skinny-ass waiter. “J.J. here. We met recently when I was visiting and I’d like to speak to Mama Cass. Please.”

“She’s not available right now,” Pigeon sniffled.

“Well when might she be?”

“How should I know? She’s a busy woman.”

“Right. Well, how about Moon? Is he around?” J.J. changed her tack.

“Look, you’re the one he calls Bones, right?” Pigeon was whispering conspiratorially now. “I don’t mess in any business but my own. But I’m giving you my professional advice, free. You want to talk, you get on in here, and don’t say you heard it from me.” Then the line went dead.

Set in the era of Woodstock and Watergate, Melanie’s Song centers on a young woman’s mysterious disappearance, and on her friend’s determined search for her.

Melanie, who fled her marriage to a straight-laced classical musician in order to hitch-hike to Woodstock and San Francisco, was last seen at a commune in the California hills. Rumors abound: that she took up with a Black radical; that she had his child; that she and her lover, armed, ran a bank heist a la Patty Hearst; that she developed a mystical gift for spiritual healing; that she died in a possible accidental, possibly staged commune fire.

Trying to sift truth from invention pulls her friend, the young reporter, J.J., into the underbelly of the sexual and social revolutions of the 60s and early 70s, where she encounters corrupt cops, paranoid hippies, activists, mystics, drug-runners,and most astonishingly, Melanie’s own parents. Risking her job, her connections, her life, J.J. follows Melanie’s trail, determined to find out what happened to her once-compliant friend now turned, it seems, into a rebel angel.