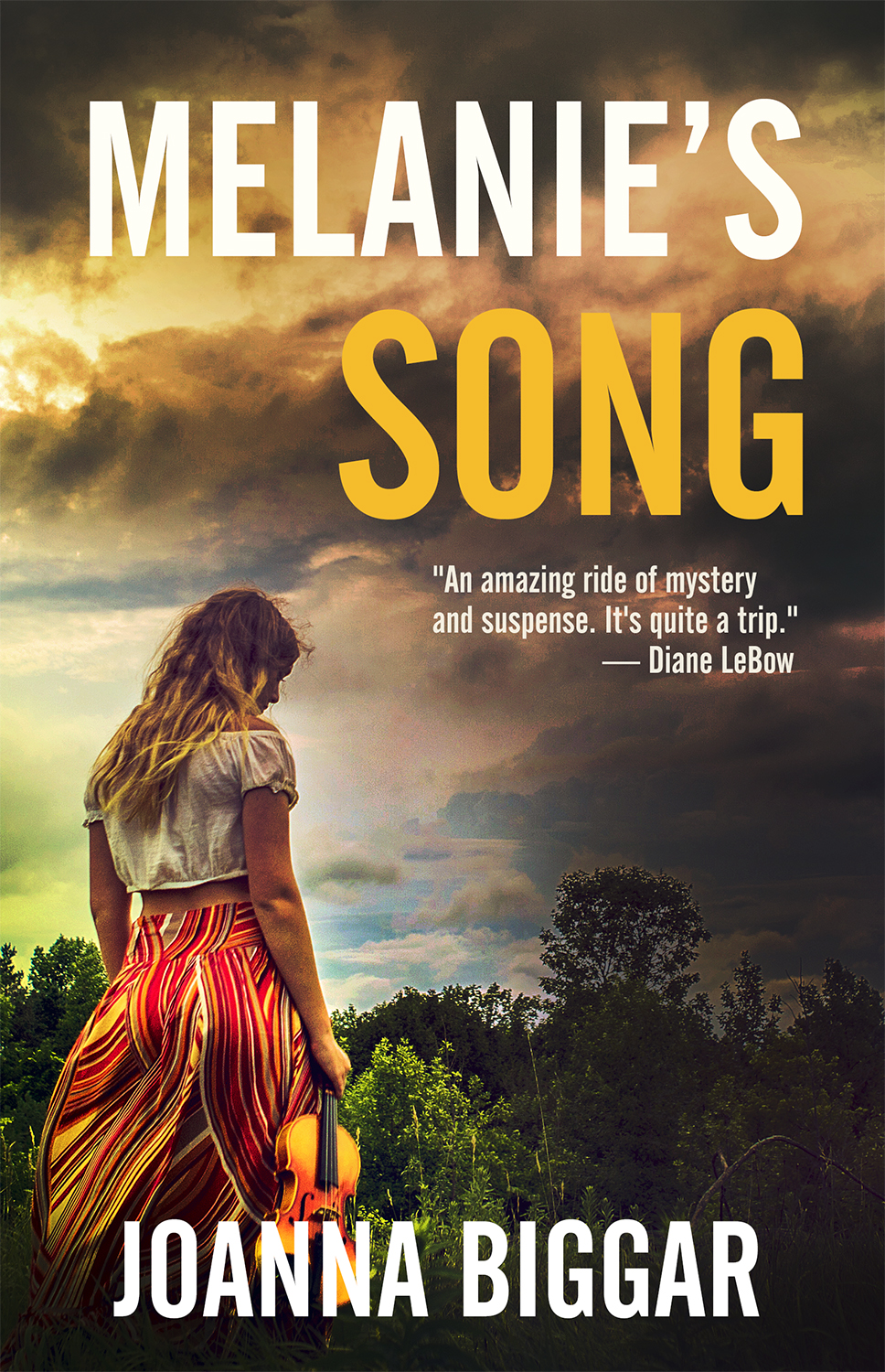

The Existential Experience of Mystery: Joanna Biggar on Her new Novel "Melanie's Song"

"I was attracted to the mystery genre not just because I love mysteries but because I think mysteries are at the heart of everything" Joanna Biggar

A missing girl, a cultural revolution, a friend tangled in the mysteries of both. How did Melanie, the most reserved of the group of young women Joanna Biggar first introduced us to in That Paris Year, become a folkloric figure of so many stories: all at once a revolutionary, a young mother, a bank robber, a mystic and a spiritual healer?

Joanna Biggar's new novel Melanie's Song, her first foray into the mystery genre, endeavors to answer this very question, but not in the way one might think having read the more conventional mysteries of the 20th century. In Melanie's Song, there is no bad guy, no definitive arrests, nor unmasked monsters. Recently, Joanna Biggar sat down with us to explain her unique take on the mystery novel.

“I have consciously tried to adapt each [style] to the type I perceive it to be. Actually, That Paris Year does draw on the Proustian tradition of long, unwinding sentences, as you say, and the words that probe the twists of time and memory, while Melanie’s Song tries to find language suitable to the mystery and the uncut dialog of some new and rough-hewn characters.”

ASP: This was an answer to a question posed the last time we sat down to talk. What do you mean when you say "language suitable for the mystery"?

JB: Time and memory are one of the underlying themes of That Paris Year. We have a first-person narrator in J.J., everything being filtered through her vision. Things were, in places, shown through other person’s [perspectives], but it was certainly focused on how [J.J.] was experiencing them. So that gave it a more cohesive tone I think in terms of how time and memory were perceived and enforced how she saw things at that point rather poetically.

First of all, [Melanie’s Song] is not in first person, which is one of the stylistic things that is very different [from That Paris Year]. It is in third-person where many things are shown from her [J.J.’s] perspective but also from the perspectives of many other characters who all speak in their own voices. We meet a lot of characters who are, as I said, sort of rough-hewn. For instance, Mama Cass brings a different kind of more real and honest element to the [narrative]from the get-go, as, for example, when she tells J.J. not to fuck up her meeting with Moon.

"When she puts herself in the role of a journalist which requires a very different skillset, to concentrate on only the facts, this becomes an approach that’s constantly failing her because she’s denying that other part of herself."

ASP: Why bring in a less poetic style with Melanie’s Song?

JB: One of the principal characteristics of J.J., the lead character, is that she has a very poetic nature and tends to see things through that lens. So, when she puts herself in the role of a journalist which requires a very different skillset, to concentrate on only the facts, this becomes an approach that’s constantly failing her because she’s denying that other part of herself.

The coming of age story of [That Paris Year] describes a poetic [outlook] which is most accessible to J.J. before having to face the many different realities and layers of Melanie’s story. Paris, France also invites that. But, the landscape of Northern California is dramatic and romantic too in a different kind of way; in a word, her language [and so the language of the novel] is different here because she’s acting in a different role, that of reporter, detective, and in some cases, spy.

ASP: Was it quite a different personal experience writing Melanie’s Song as opposed to That Paris Year?

JB: Absolutely. Very different. I wanted a change in the second one. I wanted to focus on a very different character. I chose Melanie for a couple of reasons: one, because in a sense she was the most well- behaved in That Paris Year. She came from a wealthy background and was very conventional in the way she presented herself in the world. And yet, she had this underlying and burgeoning sense of social conscience and understanding that there was something more than the cocoon she had grown up in. And I thought this contrast would be a very interesting one to focus on--it certainly played into the setting, as well, once the narrative expanded [to include the cultural shifts of the 1960s]. For instance, one thing that came out of the women’s revolution was that “well-behaved” was not the way you wanted to go. And there’s a mystery in that sense, that, how did she end up going so far from where she started? And it’s also a mystery to have the central character [titular Melanie] not really appear. It becomes partly an epistolary novel: there are many exchanges of letters, journal entries and actual published articles of J.J.’s. And I thought it was very interesting in a mystery to have this main character presented from all these disparate points of view—everyone has a different idea of who Melanie is and each has a unique story of their encounters with her.

ASP: How does Melanie’s physical absence in the narrative affect the mystery?

JB: I think that because she isn’t really there with the other characters that where she is and who she is and all the things that J.J. is trying desperately to figure out about Melanie start to exist in speculative interpretations of data about her—memories, letters, clues which may or may not be purposeful in all the trails she leaves. The person, the character of Melanie, becomes a more open question.

Her role is central, the focus being on finding her is the focus of the novel. J.J., holding Melanie’s threads, leads us through the whole narrative. But Melanie also, as J.J. acknowledges while going back through all the things she’s written, has a huge amount of insight about where everyone else is and what their characters are really like. Melanie writes up a long meditation, basically asking herself: “What’s with us? We are at a certain age now, and although society expects it, none of us has gotten married and had kids?” She meditates on these big things to the extent that it startles J.J. because J.J. has always seen her own role in the group as the “chronicler,” as she calls herself, and now it appears that Melanie has taken on some of the big questions and has some profound insights. The novel starts off as a quest to seek what happened to Melanie. J.J. quickly realizes that it wasn’t just a question of where Melanie was but of who she was, and the others are forced to re-examine their lives as part of the process.

"Our ultimate existential experience is a mystery, and I wanted to reflect that"

ASP: Were you often meditating on your own identity while writing Melanie’s Song?

JB: That’s a really good question, but I would have to say no. At the time I was writing it, which was recently, I was much older than these characters, so I don’t think what the characters were dealing with is what I’m dealing with right now. But that questioning and defining is a thing that goes on throughout various important times of your life-- it must.

ASP: Do you see young women of Melanie and J.J.’s age reading this and asking these questions of themselves?

JB: I would hope so. I mean, [Melanie’s Song] is also a period piece, so they [the characters] were experiencing their lives in a certain context during a particular period of time which must seem very far in the past now. But the questions about women and their roles and their work are ongoing. And in the novel, we do have this child and a mother who is not there to claim the child, and then a couple who are lesbian stepping up for the child despite all the difficulties. The issues of identity, courage, political activism, relations between the sexes, gender roles, meaningful careers, parenting are all in the novel, and they’re all very current today.

ASP: Why were you attracted to the mystery genre?

JB: I was attracted to the mystery genre not just because I love mysteries but because I think mysteries are at the heart of everything. Life is a mystery. We live with increasing revelations, from the origin of our species to the origins of our universe, of the unknown. We think we know something, that reality changes, and the earth just spins us. Our ultimate existential experience is a mystery, and I wanted to reflect that. I wasn’t writing a traditional mystery in the sense that, “ok here’s the question, here’s the leadup, the false dead ends, and here’s the answer,” because in this case one mystery just leads to another and the answer is a mystery itself. It’s that perpetual sense of living with mystery that I think is one of the fundamental joys and perplexities of life, so I found that I didn’t want to resolve everything. And there is a lot that is unresolved in these books, particularly with the character of J.J. which I knew from the beginning. As you can see, she doesn’t really have a name, just a couple of initials. There are things in her life she is always trying to find the answer to that she never really puts together, but she keeps trying. There’s no tight definition here. There’s something open-ended about her and about this process and about any resolution to it.

ASP: What mysteries have influenced you?

JB: Particularly, I love the dramatized ones. I find I am drawn to a lot of English literature writers. A writer who really affected me and who I’ve revisited interestingly is Daphne du Maurier. A French name but she was an English writer of the ’30s, very, very popular. [Her classic book], and the one that was gripping to me, was Rebecca. The elements of that book that I think are so attractive are classic for a good mystery: first there’s a great sense of place-- her stories are born out of the very rocky, foggy, stormy coastlines of Cornwall. And she has extremely strong characters. Often, it’s the detective in a good mystery who stands out, but with du Maurier it’s the characters in her narrative who are bold and memorable, such as Rebecca herself or the unforgettably creepy housekeeper, Mrs. Danvers, or the young woman narrator who becomes the second Mrs. Maxim de Winter. The interaction of the characters are so carefully drawn, they create a huge sensation of suspense. Another of du Maurier’s novels was picked up by Alfred Hitchcock and became The Birds.

I’ve Loved a lot of P.D. James. Some of Agatha Christie’s characters are fantastic—think Mrs. Marples and Poirot-- as are the women in Dorothy L. Sayer’s Gaudy Night. The mystery writers I tend to admire most are women, which I didn’t realize until we had this interview

“Joanna Biggar explored Paris as a post-adolescent during the distant Age of Kennedy in That Paris Year. Now she explores the backwaters of American revolutionary culture during the so-called Summer of Love in Melanie’s Song. With wit and aplomb, Biggar reminds readers that love may be free but has its consequences. A poet and journalist, when she turns her talents to storytelling, the result is a page-turning novel where mystery meets self-invention. Voila! C’est formidable!”

—David Downie, author of A Passion for Paris and The Gardener of Eden

“In Melanie’s Song, Joanna Biggar takes you on an amazing ride of mystery and suspense. Personal turbulence is masterfully set against the reality of the politics of the 1960s and ’70s in the USA. Her writing, both crisp and lyrical, draws you into each scene with tempting detail. Of course, there are those earlier memories of Paris. It’s quite a trip.”

—Diane LeBow, President Emerita, Bay Area Travel Writers