Lost in Okefenokee

A Travel Tale by Linda Watanabe McFerrin

When I was a blithely disobedient little girl, my father would always threaten, with a malignant air, to throw me into the Okefenokee Swamp. He could not know then, and doesn't know to this day, I'll bet, how thrilling a prospect that seemed. O-k-e-f-e-n-o-k-e-e. The very name was magical, and I rolled it around in my mouth with other delicious words like "Ubangi" and "Kilmanjaro." It is possible, in fact, that my unspoken desire for that forbidden place was the secret font of all my future misbehaviors.

Years passed, and I almost forgot about the Okefenokee and about swamps in general. That is, until I arrived one midnight at the Valdosta airport on a then all-important corporate job. Dead tired and cranky, I sarcastically (that's how I channeled my hostilities in those days) asked my cab driver what sights there were to see in Valdosta, Georgia.

"Well," he drawled, "not far from here, there's the Okefenokee Swamp." He said this, I think, with the same tone that my father had used on his ill-behaved daughter, but the subtlety was lost on me at the time.

I had enough sense not to insist that the cab driver, to whom I'd just been so rude, drive the 120 miles west so that I could try to wander into a swamp at midnight. But, a flame had been fanned on a very old fire. A new Okefenokee fever consumed me.

The Okefenokee swamp is one of America's largest wetlands. Covering 438,000 south Georgia acres—an area roughly one-third the size of the Everglades. It is really not a swamp at all, since it fills, flows, and drains, but an enormous watershed around 12 feet above sea level, and source of two large rivers: St. Mary's and the famous Suwannee (read Swannee) River. The name Okefenokee is of American Indian origin. It means "land of trembling earth." As the Indians discovered, "land" in the Okefenokee is not land as we know it. The swamp is comprised of over 60 spongy, peat moss formed islands, bearing colorful names like Black Jack, Roasting Ear, Broomstraw and Bugaboo; a similar number of lakes, innumerable watery glades called "homes" or "hammocks", and around 60,000 acres of grass-covered marshland.

You will know when you're nearing the Okefenokee Swamp. If you are driving up from Orlando, though well-manicured north Florida, for example, the scenery will go through a dramatic transformation. On either side of the road, you will notice narrow channels that widen into still ponds of mahogany-colored water. You might see the snakelike silhouette of an otter clinging to the trunk of one of the skimpy cypresses that rise from the ash-colored muck, or an egret, neck curled into a perfect question mark, poised on the grassy marshland. Towns will become tiny and haphazard, the landscape increasingly savage.

The Okefenokee Swamp can be accessed through any of three entrances—the western entrance, at Stephen Foster State Park, is just off Highway 29, on the Jones Island, near Fargo, Georgia. It is wilder than the park's situated to the north of Coehouse Island, 15 miles from the town of Waycross. This was the stomping grounds of cartoonist Walt Kelly, creator of Pogo, the savvy comic strip possum, and ancestor of Opus, whose arcane speech and strange wisdoms, along with those of his swamp critter cohorts, edified a generation. The eastern entrance is at the Suwannee Canal Recreation Area, headquarters of the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge. All three entrances are wild and beautiful points of ingress that include picnic areas, nature trails, guided boat tours, canoe rentals, and interpretive centers where you can gather an assortment of free and purchased literature about the Okefenokee. You will need this information to penetrate the swamp's mysteries—chances are much of what you see will be new to you. Or, you can opt for one of the guided boat tours, and a well-informed ranger like Pete Griffin will introduce you to this watery world.

Beyond that, you will need all of your senses, for the swamp of flora and fauna is as rich as a great bouillabaisse and as profoundly satisfying. It is a strange mixture of the dreadful and the sublime—a place where 300-pound black bears tread the same cypress and mulberry glades through which black-tailed deer delicately spring; where 700-pound alligators cruise canals in which egrets, ibis, herons (yellow-crested and great blue), and sandhill cranes gingerly wade. Regal flags of purple iris spring from the same mud that nourishes the hair-covered, liquor-filled basins of carnivorous pitcher plants; and lilies open like celestial white crowns next to the sticky tongues and yellow flower-lipped chambers of sundews and bladderworts, floral prisons baited for insect prey.

A fly fisherman's heaven (the season is year-round) the waters teem with catfish, bluegill, bass, walleye, trout, and pickerel. A clever fisherman will study the webs of orb weaver spiders and see what's caught in them to know just what lures to tie.

If you are wise, you will gather the literature, study it, walk the trails, bring in a picnic, and take one of the guided boat tours. If you are of a more adventuresome spirit, you will rent a two-person canoe and paddle in on one of the several trails. Some of these run the breadth of the swamp and take one to five days to traverse. Platforms along the way at 5 to 10 mile intervals have been set up for camping. The longer trails are regulated and limited to one canoe a day. This is really the best way to see the swamps, but not something to embark upon lightly.

When I finally made my journey into the swamps, our canoe barely squeaked past a 14-foot alligator, hogging a narrow channel. Less than a paddle length away, it watched us suspiciously as we tried to maneuver past, snorting water from its nose flaps and submerging like an enemy submarine until only its eyes were above the water. It was as long as our canoe. I imagined I would have fit comfortably into its gullet, more so after a couple of snaps. We capsized in a bog. The water was warm and brown and I couldn't get out of it fast enough, finally finding a foothold on spongy earth. It was an experience that lends new meaning to the expression "up to your armpits in alligators," one that I do not regret, but don't care to repeat. In a way, it fulfilled an old prophecy. I lost a roll of film on the muddy bottom and had to right the canoe and paddle on, in an attempt to recapture some of the shots. Paddling on was no problem. The swamp draws you into it. It's easy to become disoriented, absorbed in the hypnotic twist of its labyrinthine waterways, in the molasses-dark mirror of its waters, in the operatic grandeur of its tattered curtains of Spanish moss, its golden carpet of grasses, its wildlife cast of thousands.

In your small boat, you are pulled toward the canter. Its silence surrounds you, a silence broken only by the screak of insects, the muffled splash of an alligator moving into the water. The swamp has a delectable languor that is soporific. You lose track of time. And you can lose yourself there. In fact, it's easy to get lost in the Okefenokee, and once you do, it's easy to stay lost, even though you think you have left it behind, and you are thousands of miles away.

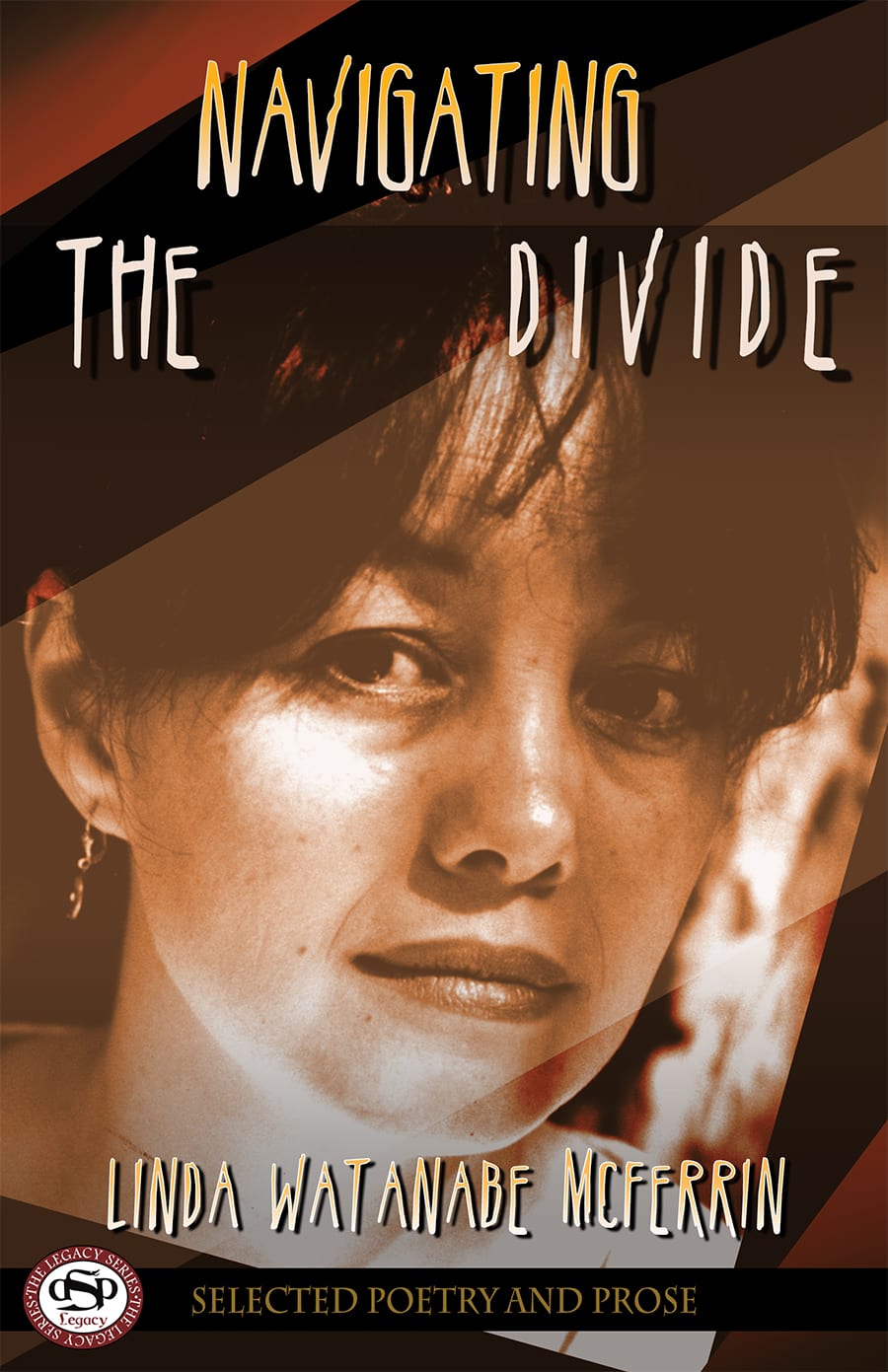

“Reading Linda’s work is like being mesmerized by a snake before it swallows you whole. The words shimmer, creating a dreamscape where the story unfolds and draws you in while strange, sometimes bizarre, encounters play out in minutely described detail. You ‘emerge’ from her stories rather than ‘finish’ them. The poems are spare, elegant and evocative, stirring deep emotions even while not ostensibly emotional. This is a beautiful book by a writer who has honed her writing skills and knows precisely how to wield them.”

—Maureen Wheeler, Co-Founder of Lonely Planet Publications

Navigating the Divide is a career-spanning, multi-genre collection from the award-winning indie literature legend, Linda Watanabe McFerrin. In poetry, essays, and fiction that are often profoundly personal and astoundingly surreal, this world traveler and literary explorer busts walls, erects bridges, and ambiguates genre. This multi-faceted collection sets out to attempt its namesake, to “navigate the divide” – between spiritual and physical, between thought and desire, between individual and collective.

Hear Linda Watanabe McFerrin Read Her Apocalyptic Poem “Sakura no Sono”

Hear Linda Watanabe McFerrin read her apocalyptic poem, “Sakura no Sono” featured in her upcoming compendium “Navigating the Divide.”

Linda Watanabe McFerrin’s “This August” Ushers us into the New Month

Today’s Featured Poem is “This August” by Linda Watanabe McFerrin.

Linda Watanabe McFerrin Breaks Down the Art of the Book Introduction

Linda Watanabe McFerrin breaks down the components of the introduction and explains its function in her newest book, “Navigating the Divide.”