Rose Solari Reviews 4 Books for The Washington Independent Review of Books

The review cycle, called "Pieces of the Whole," concerns 4 new poetry collections, each one exploring a unique theme.

ROSE SOLARI's first round of reviews in her new monthly series is live on the Washington Independent Review of Books' website and can be read here. In April's installment, the poet gives her thoughts on collections which develop a theme over many poems. She reviews the "formal mastery" of Katherine Barrett Swett’s first full-length collection, Voice Message (Autumn House Press); the jazz-infused and righteous anger of John Murillo’s second collection, Kontemporary Amerikan Poetry (Four Way Books); the "long, tumbling lines" of Matt Morton’s debut collection, Improvisation Without Accompaniment (BOA Editions); And finally, the "warm and urgent" Rue (BOA Editions), Kathryn Nuernberger’s third book.

You can check out an excerpt below from her review of Voice Message. As this is a monthly review column, be sure to check back for Rose's May reviews.

Excerpt:

Rose Solari's poetry is available now in a convenient three-book bundle. For the time being, all shipping in the US is absolutely FREE.

Rose Solari's poetry is available now in a convenient three-book bundle. For the time being, all shipping in the US is absolutely FREE.

Buy The Rose Solari Poetry Bundle

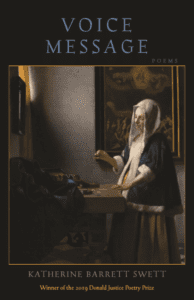

Katherine Barrett Swett’s first full-length collection, Voice Message (Autumn House Press), is a tour de force in which formal mastery is wedded to emotional power. The book is centered around the death of the poet narrator’s daughter, but if you’re thinking we’re in confessional territory here, think again. Swett is a formalist in the best sense, using her skill — particularly with sonnet form, the predominant form used in the book — not to distance the reader from experience, but to distill it for us.

Katherine Barrett Swett’s first full-length collection, Voice Message (Autumn House Press), is a tour de force in which formal mastery is wedded to emotional power. The book is centered around the death of the poet narrator’s daughter, but if you’re thinking we’re in confessional territory here, think again. Swett is a formalist in the best sense, using her skill — particularly with sonnet form, the predominant form used in the book — not to distance the reader from experience, but to distill it for us.

The central of the book’s three sections, “Vermeer’s Daughters,” is occupied by that demanding sequential form called a royal crown of sonnets: an interlocking chain of 15 sonnets, in which the last line of each of the first 13 poems is also the first line of the next; the 14th poem concludes with the first line of the first poem; and the 15th and final poem is composed of the first lines of all the previous poems in order. Swett navigates these challenges with breathtaking ease. No rhyme feels forced, and every image shimmers.

Each poem in Swett’s sequence takes on a different painting by Vermeer, each featuring a girl or young woman. The tone is both elegiac and celebratory, the narrator sometimes allowing her own grief for her daughter into a poem, then slipping away again, as in the opening of “Young Woman with a Water Pitcher”:

Just as the liquid pours but never sinks,

I every day defy the gravity,

deny there’s any reason why I blink

except perhaps a mote caught in my eye.

Behind her form, the map and sun-splotched walls,

the lightness where her dark dress is immured;

outside the colored glass, the morning calls

of sailors and the slap of boats secured.

How subtle the reference is to the narrator’s unshed tears in the opening lines, how musically appealing the rhyme of immured and secured. And, as in every poem in this royal crown, the poet deftly suggests the world behind the painting, evoking the sounds of life outside the frame.

Grief is of necessity about absence, and yet this elegiac book is also richly peopled. A pair of villanelles for the lost daughter in the book’s first section gives us vivid glimpses of what’s missing. From “Flute Song,” for example, the lines “And when we she played she lightly swayed her hips / and kept time softly with her slippered foot” are precise in image and also so deeply musical, with the internal rhyme of played and swayed, the consonance of softly and slippered, that I found my body moving with them as I read.

And in “Winter Light,” in the lines “your brother smiles and something in his mouth — / I think death left behind a bit of you,” the dash between lines creates an added suspense to the line break, the promise of smiles now cruelly yanked away by death.

The book concludes with a section of poems about mythological and fictional characters and literary figures from the past. Again, the sonnet form predominates but never grows tiresome. With her first full-length collection, Swett establishes herself as a poet of great skill, with a keen ear and a wise eye. This is a stunning book.