ASP Celebrates AAPI Month With Selections from the Work of Linda Watanabe McFerrin

ASP celebrates Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month with works by Japanese-American poet and writer, Linda Watanabe McFerrin. The two poems and one essay below are featured in her Legacy Collection, Navigating the Divide.

LEGACY

I.

In the first act, remember her madness—

her wide gash of sorrow, her obi of blood?

The tragic Kabuki heroine,

she committed seppuku,

hid the cross-wise cut

under mulberry robes.

We walked like obakes, like unsettled ghosts.

She cut my long hair. It frightened her.

It stole the first scene of the play.

She made me wear wooden clogs.

She plucked out my eyebrows,

so that people would mistake me for the moon

II.

In the second act, she unwound her obi of blood

and wrapped it around me,

tied my hands and my ankles.

Not even my weeping could wipe it away,

could bring her back from the realm of the dead

where she’s wandered as long as I’ve know her.

She said “We should all have died at once.

We should lie in a common grave.

III.

In the third act, she made and unmade me,

told me again of her deep, bitter wound,

said, “This is your legacy, daughter.

Let the anger boil up inside you,

let the red pour from your ears and your eyes.”

She drained me of color and sutured my heart.

I rang like a bell. “Sorrow. Sorrow.”

IV.

In the fourth act, the psychiatrist entered.

I thanked him and gave him black stones.

I added them to the scales on his desk.

I discovered that none of his patients survived.

“Look,” I said, “I’m better”

“Yes,” he said. “Let’s pretend.

EPILOGUE

In the epilogue, I am walking along a seashore.

I’m pretending that beauty can reach me.

I’ve thrown out the kimonos, the costumes and robes.

I’ve made a new self out of flowers and surgical steel,

a shiny new self that blooms every spring.

And I’ve cast all the ancestors

back over the sea,

like pearls.

They are pain.

They are sand.

CHINA-JIN

(China people)

“China-jin,”

my mother hisses the word

as they pass by, faces like yellow pears.

She shakes her grey head,

now grown wobbly as theirs—

the old ones,

the ones she whispers about.

At times the neighborhood I live in

is Shanghai or Canton,

and she, a child again, a half-caste

Japanese-English girl with black hair

shiny as a myna’s wing, an alien

in a sea of similar-seeming ivory and almond.

She straightens, pulls a long face,

like a lady walking past a fish market

tightens the nostrils of that hooked patrician nose.

Her Anglo-Asian lids fold downward.

Sometimes I hear her rattling away in rusty Mandarin,

then Cantonese, her dry voice rising and catching,

an uppity settling on her audience:

a Chinese woman at the local market,

where she has found daikon,

the long white radish that she loves.

The desperate scattering of language—

hoping it meets with smiles and deferential nods

like the “oohs” and “aahs” of the Chinese kids she gave her

toys to—

she counts these memories as her only worthwhile heirlooms.

An old Chinese man winks at her.

She stiffens, mutters “China-jin,”

this time a clucking deep inside

around the secret pleasure

of being mistaken for one of them.

IN TOKYO, FINDING THE KAMI WAY

Rainfall and the raw complaint of crows threaded through the silence that filled the tiny haiden or hall of worship at Ueno Toshogu Shrine. From somewhere on the tree-canopied walkways that circled the shrine grove, the chatter of women and laughter of children wafted in on the mist. More faintly still—almost inaudibly—autos made their whispery way over wet city streets. In the quiet of that Shinto shrine in the heart of Tokyo, the nearly 12 million people who inhabit the metropolis (San Francisco’s population is around 740,000) seemed to be little more than a dream.

No dream, my arrival in Tokyo had been very much a reality and a pleasant one—the gentle ministrations of the Japan Airlines staff, the clockwork arrival and efficiency of the airport shuttle that whisked me from Narita along the Expressway, over the Rainbow Bridge and deposited me in what looked like Tomorrowland, the silvery sky-rise complex next to Odaiba Beach overlooking Tokyo Bay. I’d returned to Tokyo after decades of absence to see if I could find something that had eluded me in my childhood, some secret about this huge city in which I’d once felt so lost. That evening, lingering over a cocktail in the Sky Lounge of the elegant Meridien Grand Pacific Hotel, I unfolded my city map to reveal the large splatters of green that indicate the city’s many parks and gardens, squinting through the flicker of candlelight to find the little goal post icons that mark the Shinto shrines. In these shrines, or jinja, Japan’s folk deities, the kami (both natural forces and humans are counted among their number), are believed to reside. It is said of the Japanese that they are Buddhist by belief, but Shinto by virtue of being, so in many ways these Shinto shrines house the spirit of Japan. I circled several, two of them in the Ginza, and refolded the map. On the other side of the moonlit waters, across Tokyo Bay, the sceptered shape of Tokyo Tower twinkled, the huge metropolis spread around it like an extravagant and glittering train.

The city of Tokyo covers more than 800 square miles, but on its vast system of interlocking train and subway lines, getting anywhere is only a matter of minutes and a couple of dollars. The next morning, 310¥ or around $2.25 at today’s fluctuating exchange rate, took me from Daiba Station (across the skywalk

from the Meridien Grand Pacific) to Shimbashi Station on the monorail, a dove-and-mauve plush 10-minute ride past towers of glass and concrete. From there, another 130¥ and a few more minutes got me to the Ginza, one of Tokyo’s trendiest and most popular shopping districts. The Café Odiri—a lovely

European-style watering hole at the foot of the Printemps. Department store, was a great place to get my bearings. Next thing I knew I was one of the butterfly crowd, flitting from kimono shop to gallery to designer boutique as I made my way down Sotobori-dori Avenue. Carried away by material enticements, I almost drifted right past Ginza Hachikan Shrine. Situated on the first floor of an eight-story office building and not much larger than a closet, its diminutive dimensions came as something of a surprise. Missing were the cypress and pine that usually surround Shinto shrines. Nature’s sanctity and man’s harmonious coexistence with it are such an important part of the Shinto belief structure that its places of worship almost always incorporate some homage to this relationship. I wondered if the abstract paintings that filled the vitrines on one of the walls were supposed to fill that purpose.

Other features typical of Shinto shrines were compactly represented. A white-and-gray-clad Shinto priest, chanting solemnly to himself, manned a counter upon which wooden prayer tablets and other types of offerings for purchase were displayed. I bowed respectfully, and watched as a young working woman in a cream-colored suit stepped in from the street, cleansed hands and mouth at a small stone fountain and positioned herself in front of the sanctuary. Looking very much like the raised entrance to a fine Japanese home with a place for offerings in front of it, this sanctuary, or honden, is where the kami is believed to reside. The young woman cast her coins into the offering box, rang the large bell rope to get the kami’s attention, clapped her hands three times, bowed and clapped again. The ritual seemed perfunctory, a matter of habit. A few steps away the city rushed by.

Only a few of the shrines that I planned to visit were in the southeastern part of Tokyo. To visit Meiji-jingu, the capital’s greatest shrine, I decided to take up residence toward the west, at the juncture of what were once Tokyo’s most important roads. Even after Odaiba Beach and the Ginza, the fastpaced Shinjuku district with its skyscrapers and towers, came as a bit of a shock. Entire cities exist within the walls of some of its 40 and 50-story edifices. Shinjuku Station, right across from the Keio Plaza Inter-continental, my home for the next few days, is easily the busiest station in Tokyo. Approximately two million people pass through it each day. My dazed walks between business towers and fountains and past sex and cinema entertainments took me to Shinjuku Park and to beautiful Hanazono Shrine. Not far from Shinjuku, a short train ride on the Yamanote line—is Meiji Shrine, Tokyo’s grandest, completed in 1920 in memory of Emperor Meiji, the ruler credited with the modernization of Japan, and his Empress. Only a two-minute walk from Harajuku Station, Meiji-jingu is impossible to miss, the thirty-three-foot single cypress pillars and the 56-foot cross-beam of its monumental torii gate dwarfing everything around it. People streamed, looking small as ants, through it and down the wide walkways. Right behind the shrine complex, 133-acre Yoyogi Park was the perfect spot to sit and ponder the experience. Clouds of hydrangea floated in the patches of shade that framed stone picnic tables. Groups of students—young and old—practiced everything from violin to tai chi.

In spite of the shrines, in spite of the superlative service and uptown charm of my hotel, Shinjuku was wearing on me. I craved a quieter atmosphere. I knew just where to go. Packing my bag and taking subway and train once again, I headed northeast, toward Taito-ku, to a simple, but much-recommended, ryokan or traditional Japanese inn. Visitors unfamiliar with Japan often have the misconception that Japanese ryokan are expensive places to stay. They needn’t be. At Sawanoya Ryokan, a comfortable room with shared toilette and Japanese bath costs only ¥4700 or $34 a day. Mr. Isao Sawa, the establishment’s amiable proprietor, greeted me warmly upon my arrival and took me upstairs to my room. Morning sun filtered in through the creamy rice-paper panes that screened the windows. On my bedding, a Japanese summer kimono or yukata waited, folded and pressed. On a low round table, or ozen, teacups, tea pot, hot water and green tea leaves promised a soothing respite. When I closed the door, the smell of freshly woven green tatami mats rose up around me. I studied the hand-drawn, hand-lettered map that Mr. Sawa had given me. Umbrella shops, book stores, bakeries, bathhouses, tatami makers, noodle shops, florists and a host of temples and shrines crowded the page. I’d found just what I wanted—a folksy, oldfashioned Tokyo neighborhood.

It was easy to rise early every morning, to drink my green tea and head out into the close-quartered maze of little businesses that made up my new environment. Nearby Nezu Shrine proved the perfect place to spend a sunny morning before lunching on zaru soba—cool, tri-colored buckwheat noodles—tempura and ice cold sake. Another day, my backpack stuffed with goodies—little cakes with delicate swirls of sweet been paste and golden sembei crackers in their sere, seaweed wrappers—from the neighborhood shops, I occupied long hours visiting shrines in the Asakusa district. The cramped streets of Asakusa, dense with merchants, are typical of Shitamachi, or the old downtown, when Edo—as 19th century Tokyo was called—was the Shogun’s power seat and the Shogun, not the Emperor, ruled Japan. I strolled along the

Sumida River, watching the ferries cruise down toward Odaiba Beach, toward the “river gate” that had given Edo its name. In the evenings, I sampled the tasty and quite inexpensive fare of local restaurants and pubs and followed my gregarious landlord through the labyrinth of alleys, as he guided me past private shrines and cemeteries, telling me ghost stories, his wooden geta or sandals clicking before me as he led the way in the lamplight.

One rainy morning, I headed south along Shinobazu-dori Avenue, toward Shinobazu Pond, the Shitamachi Museum and the nest of temples shrines and museums that dot Ueno Park. When I’d visited the park as a child it was only to go to the zoo. I remembered it as a great place for children, but it is a fine destination for people of any age. There, I stopped at Ueno Toshogu Shrine, stepped into the haiden and hesitated, stocking-footed, beneath the gold and cobalt portraits of warriors, princes and philosophers and listened to the rain.

I had been in Tokyo for nearly two weeks. A few days before leaving, I moved back to its center, to the Capitol Tokyu Hotel in Chiyoda-ku close to the Diet, the Japanese ministries and the parks and gardens that surround the Imperial Palace. A grand location and an entertaining one—Eric Clapton, Michael Jackson, Diana Ross and the Three Italian Tenors are just of few of the celebrity tenants who stay there when in Tokyo— its ample rooms were quite a switch from my previous residence, and they carried a much higher price tag. Still, high prices seem in keeping with a Presidential Suite with a kitchen installed so that Pavarotti can make pasta or an Imperial Suite with an unobstructed master bedroom view of Hie Shrine. My room, which was considerably smaller, also had a magnificent view. I looked straight down upon the koi pond where the fish, enormous torpedoes of silver and flame that looked huge even

from my sixth story perch, swam about in their languid circles.

Hie Shrine was right out in front of the hotel, separated from the street like most holy places in Tokyo, by a steep flight of stairs. Inside its torii gate, it was peaceful, sunlight bouncing off of the small gray stones of the courtyard. A couple of princely roosters, all amber and emerald, strutted about the grounds. I washed my hands and rinsed my mouth at the fountain, walked up to the sanctuary, rang the rope bell and clapped to get the kami’s attention. No longer hesitant, I gave my prayer of thanks, realizing at last, as I hadn’t when I was a child, that the presence of the kami is delicate like most things of value in this world. It is found within a quiet heart, one that moves effortlessly from the frenzy of daily life to the silence of a Shinto shrine, in tranquility and a profound sense of balance even in the midst of chaos.

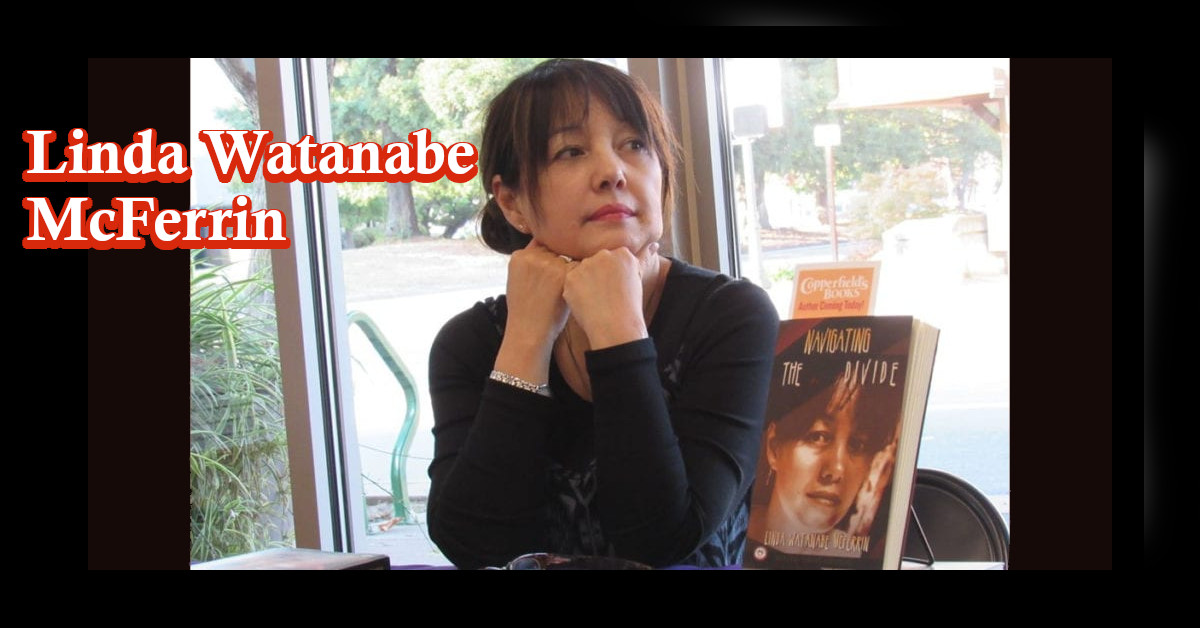

Linda Watanabe McFerrin is a poet, travel writer, novelist and contributor to numerous newspapers, magazines and anthologies.She is the author of two poetry collections and a winner of the Katherine Anne Porter Prize for Fiction. Her novel, Namako: Sea Cucumber, was named Best Book for the Teen-Age by the New York Public Library. In addition to authoring an award-winning short story collection, The Hand of Buddha, she has co-edited twelve anthologies. Her latest novel, Dead Love (Stone Bridge Press, 2009), was a Bram Stoker Award Finalist for Superior Achievement in a Novel.

Linda has judged the San Francisco Literary Awards, the Josephine Miles Award for Literary Excellence and the Kiriyama Prize, served as a visiting mentor for the Loft Mentor Series and been guest faculty at the Oklahoma Arts Institute. A past NEA Panelist and juror for the Marin Literary Arts Council and the founder of Left Coast Writers, she has led workshops in Greece, France, Italy, England, Ireland, Central America, Indonesia, Spain and the United States and has mentored a long list of accomplished writers and best-selling authors toward publication.